A friend recently asked me about what I meant many years ago about “generational praxis”. I will come back to this concept/issue later. But if you want to crosscheck Antonio Gramsci on Google, please go ahead.

He asked me this in an awkward context wherein we had listened to the new music that is now very popular with the youth of Zimbabwe and also somewhat over-similar in its instrumentation and lyrics. This music is either called dancehall or hip hop as motivated by social media.

We were in Dzivaresekwa high density suburb where I partly grew up. (I also grew up in Chitungwiza and Waterfalls)

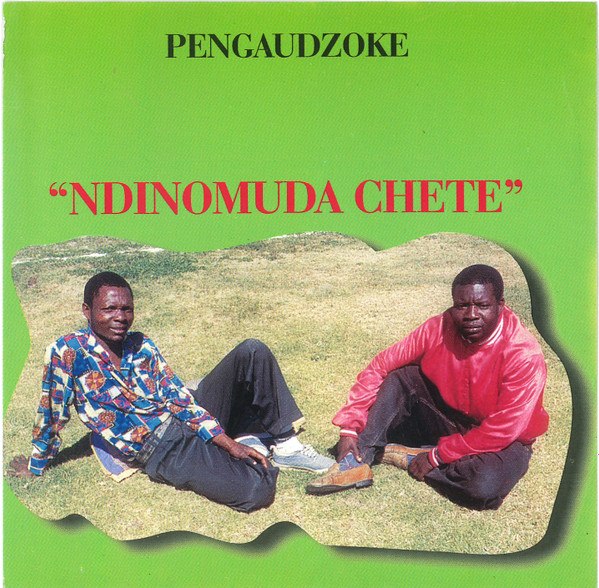

The music was blaring at the braai spot and it was not what we were used to when we used to watch Mvengemvenge /Ezomgido. Or go to watch Pengaudzoke or Somandla Ndebele live in concert at Nyaguwa nightclub. Or get over-inspired by Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited’s Chimurenga Music.

The music we were listening to was more brazenly individualistic, self-celebratory and somewhat abstract. But it suited the moment and also helped with memory and nostalgia of belonging. Both to the proverbial ghetto but more significantly of meeting with friends from long back.

In the conversations we had with my friend, I still looked around at the evident poverty of the neighborhood and its contradictory pride. Almost as though, in our dancing and inebriation, the cdes were saying, as in the songs they were dancing to, “ This is who we are! We were born here”

Lyrics that are also derived from popular musician “Killer T” who represents an iconic figure of both recognition of origin from the ghetto but also departure from it. Only to return in pride to prove that things worked out well elsewhere.

This is not a new comparative argument for many Zimbabweans. We all encounter it at church, work and in social spaces. Sometimes with individual pride and competitive work experience. Or in some cases with individual envy and competitive desire to be better than the ‘other’. Be they from high school, college or university.

It is a very interesting paradox. That is, to want both life experiences in post-independent Zimbabwe. You were born, grew up and educated in either a rural enclave or urban ghetto and now you can argue about your successful point at arrival in the leafy suburbs of Harare, Bulawayo, Gweru, Masvingo or Mutare among many other towns and cities.

This is a very realistic and emotional point to make because the majority of colleagues who went to high school, college or university between the late 1980s to the new millennium have this mindset. The ones that were the first to get colonial education before independence are probably more embedded in specific lifestyles and habits that are too ingrained in them to be challenged intellectually or socially.

But lets get back to “generational praxis” by asking the question of how do we now construct an understanding of a global progressive human existence. Regardless of race, colour, origin or class?

Within an African context.

The reality of the matter is that this has not yet happened. Mainly because of our own African materialism and regrettable simplicity over our lifestyles. As we interact with global capitalism via money, movies and the attendant re-objectification of the female body (black, brown or white).

In this, we are not learning from history. We are entrapped in a neoliberal cycle of assuming that the world is our oyster. Even as we Africans from all regions die going to the global north in the Mediterranean sea.

Or as we clamour to be recognized as equal human beings via various United Nations conventions that we fought hard for in the past and in the contemporary.

The question that however hangs over our heads is “What do we now teach our children?” And also one about, “Who teaches them?”

We all know from an African perspective that mothers are the best teachers of children. Especially in their infancy. Your first song, sense of understanding of reality always stems from your mother.

Though with the passage of time, depending on your gender, this can be ahistorically disputable.

But we need to look at the bigger picture. We need to get ourselves to quite literally believe in our being. As Africans and beyond what we see on television, Netflix, the pastors pulpit or on other social media platforms.

Even if wanted or willed it, we are not all main actors or survivors. We are a people that should treat each other with equality and fairness. In as democratic a ways as is possible beyond the bright lights syndrome but an organic understanding that progressive change belongs to everyone.

Indeed the global political economy sets out the standard for that house, car, trophy husband or wife, but it will never change the reality that life must be lived as honestly and obejctively as possible. Beyond what you see on television and social media.

Materialism is not a ‘life standard’. It helps with how an individual or individuals can be perceived in a given society but it doesn’t change much. Unless you find yourself in a church organization. Or political party with ambitions for both local or national power. Or your remember the Nkrumah maxim, “Educate a Woman, You Liberate a Nation”

The major question however is what are we teaching our children? Is the praxis of whatever we are teaching them going to make them better Zimbabweans? At this rate, it is least likely.

Leave a Reply